Automating the Office Assistant

The Office Assistant - in particular the Paper Clip character "Clippit" - has been the object of much scorn and derision1, especially by programmers. Some intrepid souls, though, having discovered that Clippit is not the only supply in the storage closet - cute little critters like Rocky the pup and Links the cat are options, too - actually like the Office Assistant. Programmers should not be so quick to dismiss the potential benefits of an Office Assistant; as part of Microsoft's natural-language Help system an Assistant can be customized to provide a narrow list of topics for a perplexed user, as well as affording innocent distraction.2

Introduced with Office 97/v.8 as "actors" (.act files), the Assistants were created by a since-absorbed company called Fundamental Arts3. Non-standard Assistants (not found on the Office installer CD) such as Earl the Cat and Kairu the Dolphin could be downloaded from Microsoft's site, but programmers could not create their own custom Assistants as Fundamental Arts kept how to a closely guarded secret. When Microsoft released Office 2000/v.9, they changed the technology behind the Assistants to the Microsoft Agent ActiveX technology, which meant that programmers could create their own Assistants/Agents.4

Automating the Office Assistant (literally "making it do tricks") is a matter of learning the Assistant Object Model, which has evolved somewhat from Office 97 to the current Office XP/v.10. Documentation on Office 975 is hard to come by, but the MSDN Library site does have separate help areas for Office 2000 and Office XP Assistant programming. For the purposes of this mini-lecture I will focus on automating the Office 2000/XP Assistant. I run Office XP on my machine, but the code should work just as well on an Office 2000 setup.

The first thing most students want to learn about the Assistant is how to make it do amusing things on command. Alas, not all the endearing gestures and sounds are controllable, but the basics (printing, searching, panic, hello, goodbye, etc.) are. If you open the Object Browser in your VBA Editor and filter for the Office library, you can scroll down the list of classes until you see MsoAnimationType. This contains all the animation ("tricks") constants. Here's a Word document* that has a procedure called MakeAssistantPerform. (Make sure your Office Assistant is turned on and visible before you click the button, incidentally.)

"But, wait!" you cry after seeing that only five options are listed, "What about all the other tricks?!?". The Assistant Balloon, which is the popup space where you and the Assistant communicate, only allows five options at most. This is actually according to Microsoft's User Interface Design Guidelines. Studies have shown that folks when presented with more than five objects will break them down into two or more smaller groups because the amount of information becomes too overwhelming to process all together. It might have something to do with us having five fingers. At any rate, it's considered bad form to have more than five options in an option group and the Assistant's balloon qualifies as an option group. If you want to see other animations, just change the code. Here's the code, by the way:

|

But how and why does this work?

Well, the top level object is the Assistant. The Assistant communicates through the balloon. There can be only one balloon showing at a time (I call this the Highlander Principle...) We use the Set statement along with the .NewBalloon method to instantiate a new balloon. You'll notice that we close the procedure with another Set statement; that one gets rid of the balloon object by setting it equal to the keyword Nothing. You should always code your Set statements in pairs like that to avoid potential memory leaks.

Think of the balloon as an elaborate message box. The .Text property is like the Prompt argument and the .Heading property is like the Title argument. The .Button and .Icon properties very similar to their message box counterparts. You can format the .Text with underlines and different colors and even use your own graphics. (Office VBA Help is pretty good about explaining how.)

To make the balloon perform a task (as opposed to just being informative) the .Mode property has to be msoModeModeless. This means it sits on top but doesn't keep you from performing other tasks - unlike the MsgBox. .BalloonType needs to be msoBalloonTypeButtons if you want the user to be able to click and choose options - the other types, numbers and bullets, are non-interactive. These buttons (or numbers or bullets) are in a 1-based array called BalloonLabels, coded as .Labels(x), where x is the item index. .Text sets the verbiage for the user. Unless you've coded an intercept (like my code does) some action will occur immediately when the user clicks one.

The balloon can also have checkboxes, contained in another 1-based array called BalloonCheckboxes and coded as .Checkboxes(x), where x is the item index. Its .Text sets the verbiage for the user, too. The checkbox also has a .Checked property, much like other VBA checkboxes, which is either False or True. Clicking the checkbox will not make an action occur without also clicking on a button.

.Show merely makes the balloon visible and it is always the last step in your balloon procedure (before the Set = Nothing, that is).

So, what's with that .Callback then? Well, that's what makes the magic happen. It points to a Sub procedure that carries out the Balloon's instructions. You create this procedure. It must have three arguments and it doesn't matter what you call them as long as they are in the correct order and of the correct data type. I called mine bln, lngButtonResult and lngButtonID, but I could just as easily have named them Squid, Octopus and SeaUrchin.

The first argument is what ties the procedure to the Balloon, so wherever you would need to refer to the Balloon, you'd use bln (or Squid, or whatever). The second argument, lngButtonResult, contains the result of any buttons clicked on the Balloon. This is a lot like the MsgBox return value. If you had an array of Button labels then the return value is the index value of the button label (1,2,3, etc.) And remember, it's always most efficient to code lists in Select Case statements. The last argument uniquely identifies the Balloon. There can be only one Balloon showing at a time, but several balloons can be shown in succession all with their own callback procedures. Even if you don't refer to the last argument within the procedure you still need to list it in the procedure definition.

.Close explicitly gets rid of the Balloon, otherwise it hangs out until being replaced by another Balloon or if the user clicks a Cancel button (defined under the .Buttons property of the Balloon). I put the .Close in a condition to execute only if the checkbox wasn't checked. This allows the Balloon to stay up so the user can go through the series of animations.

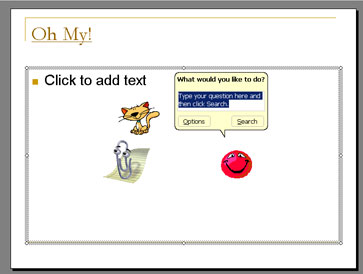

Another handy bit of code is to change the Assistant. This is in a PowerPoint document*. On XP, at least, one can get interesting results, as seen in the image below, so be prepared to end task on the agentsvr.exe process(es) if something goes wrong during testing...

The Assistants' files are located in the Office installation directory and have an .acs file extension. Here's the code:

Option Explicit |

Because folks can turn off the Assistant or just hide it temporarily, I included code to forcibly show it using its .On and .Visible properties. The rest of the code is almost exactly the same, just without the checkbox.

Just in case you're wondering, "and this is useful to my users....how????", here's another procedure to bring up a slide navigation balloon (during editing, not presentation):

|

Again, the code is virtually identical to the first example, it's just what you put in the Callback procedure that makes all the difference.

I hope you've enjoyed your brief introduction to the Office Assistant! Please let me know if you have any questions.

1See "Microsoft's paper-clip assistant killed in Denver", "When Paper Clips Attack" and "I Hate the Paper Clip Man".

2Someone in Germany wrote an academic paper on the Assistant called "Computers as tools or as social actors? -- User perspectives on the social interface"

3Fundamental Arts is now NetSage, which has merged with Finali (apparently itself no longer active).

4If you would like to develop your own Assistant/Agent, Microsoft has all you need.

5Some links to articles relating to Office 97 Assistant programming are Using Microsoft Office 97 Shared Components: The Office Assistant and ACC97: How to Animate the Office Assistant.

Alrak's Course Resources ©2002-2007 Karla Carter. All rights reserved. This material (including, but not limited to, Mini-lectures and Challenge Labs) may not be reproduced, displayed, modified or distributed without the express prior written permission of the copyright holder. For permission, contact Karla.